Solving Factorio Quality

Simon Sapin,

I play Factorio the normal way: by writing matrix math code to plan the factory.

But we’ll get to that. Or, TL;DR, go to my new online calculator tool.

Intro to Factorio and Quality

Factorio pretty much founded the factory video game genre: you play a character who harvests resources and combines them to craft increasingly complex items, which in turn enable more sophisticated crafting. So far this sounds a lot like Minecraft and many other survival games, but what sets factory games apart is the focus on automation: soon enough, most of the crafting is done not “by hand” by the character but by increasingly many machines, with various forms of logistics like conveyor belts to move items between machines or wherever they need to go. Some factory game go further and remove the player character altogether.

As “technologies” are unlocked in-game, Factorio offers many mechanisms to improve production. One of them is modules: crafting machines have a (limited) number of slots to accept different kinds of modules that affect its stats: speed modules make the machine run faster at the cost of more energy consumption, productivity modules increase yield from the same ingredients at the cost of speed and energy, etc.

Release in 2024, the Space Age extension adds a new game mechanics including Quality: every item and recipe now come in five quality tiers: ⚀ normal, ⚁ uncommon, ⚂ rare, ⚃ epic, and ⚄ legendary. Depending on the item, each tier improves stats such as making crafting machines faster or making productivity modules more productive. High-quality items can be crafted directly from ingredients of the same quality, but the only way to increase quality is through the new quality modules.

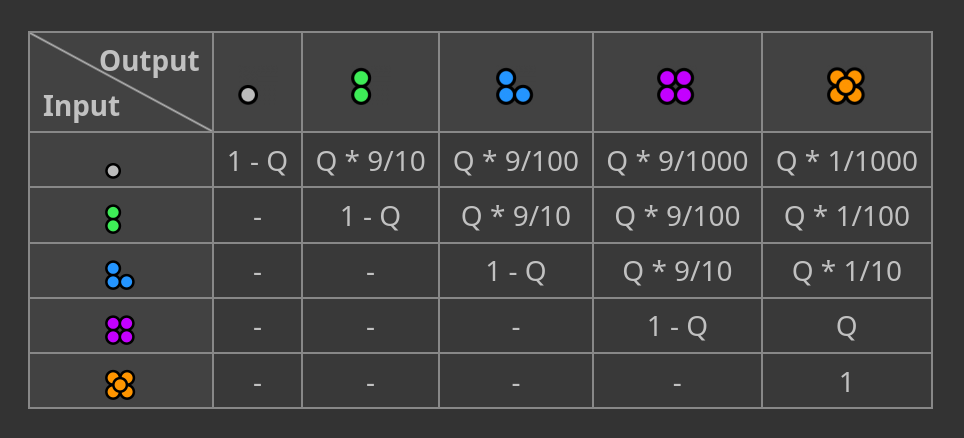

Modules affect the probability of any quality increase. For a given craft, each quality tier increase after the first is another 10% chance. We can build a table of the probabilities of output quality depending on input quality:

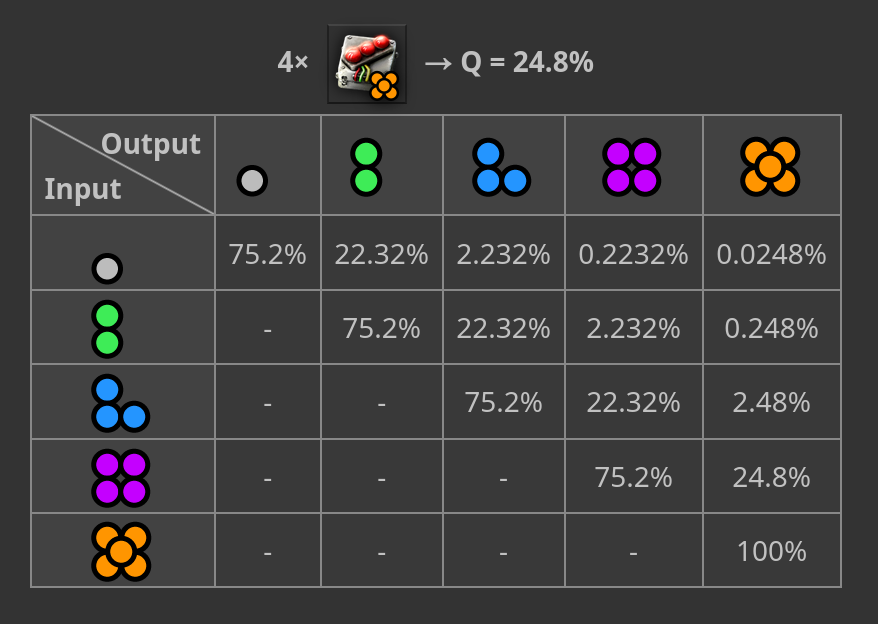

For example, the maximum possible quality chance in a machine with four module slots is 24.8%:

Some players dislike the introduction of randomness to a game that was mostly deterministic, but with enough repetitions probabilities become ratios.

The probabilities are balanced so that even with multiple crafting steps (each a potential quality jumps), getting high-quality items unavoidably involves also crafting many unwanted low-quality ones.

To avoid the factory grinding to a halt when storage eventually gets full, Space Age also introduces the recycler: a new machine that destroys any item and (usually) returns 25% of its ingredients. This enables players to design “upcycling” contraptions that craft and recycle in a loop with quality modules until items reach the desired quality, at the cost of consuming many more ingredients:

Factory planning tools

Some video games are partly “played” outside of the game itself. Blue Prince fully expects its players to keep extensive notes of everything they see, but doesn’t provide an in-game notepad or similar tool. Factory games lend themselves to building large spreadsheets for resource accounting, but a select few players decide that spreadsheets are not powerful enough for factory planning and spent countless hours programming dedicated tools that reproduce much of the game’s math to accurately a production chain.

This is all optional in factory games, it’s perfectly viable to play it by ear and just build more when seeing something lacking.

But I do like to plan in advance: how many machines of each kind do I need? How much yield can I expect? Where are the bottlenecks? The looping nature of quality upcycling makes this particularly challenging either to guess, or to calculate with existing tools.

Matrix math and long-term averages

So far we’ve looked at the probabilities of different outcomes for a single craft. As we consider more complex systems, it may be hard to keep track of many combinations of possible fates for each item. Instead, let’s rely on probabilities becoming ratios with enough repetitions and quantify average throughputs over long enough periods of time in systems that converge to a steady state.

Let’s imagine we have a conveyor belt of ingredients (for example iron plates) of mixed quality tiers (⚀ normal, ⚁ uncommon, ⚂ rare, ⚃ epic, and ⚄ legendary), as well as enough assemblers to craft them all into some product (for example pipes) with a quality chance of 10%. A product of a given tier can come from ingredients of the same tier or lower, with probabilities we’ve established above:

(The percent sign can be thought of as implicit division by 100, so that “percentage of” is the same as multiplication.)

This look suspiciously like the probability table, transposed across the diagonal. The transposition is only because we’ve arranged product tiers vertically. Instead let’s group the throughputs of different tiers of the same item into row vectors:

Now our system of linear equations can be written as a single equation where a vector is multiplied by a transition matrix that matches the wiki’s probability table:

(As an edge, , the identity matrix: zero quality chance means no tier transformation.)

This may not seem like much progress, but now a multi-step process can be computed through successive matrix multiplication. For example mining iron ore with 10 miners (initially each producing 30 / min of normal quality ore) with 7.5% quality chance, then smelting it into iron plates with 5% quality chance, then crafting pipes with 10% chance. With no productivity bonus, we get this tier distribution of end-products:

Fortunately, every game mechanic we’re interested in (crafting, quality increase, productivity bonus, recycling) has linear effects on long-term averages, so every process can be representation as multiplication by a transition matrix. For example:

Another advantage of linearity is that we can scale a whole computation after the fact. In the example above we assumed no bottleneck in smelting, crafting, or logistics; but if we decide to only allocate enough space to craft 100/min normal-quality iron plates into pipes we can multiply the whole equation by and get the expected consumption and yields for that scenario. Factorio “naturally” has back-pressure, so processes upstream of a bottleneck pause when their output buffer is full and their long-term average throughput converges to the one dictated by the bottleneck. (Compare with Mine Mogul, a factory game where conveyor belts don’t have back-pressure and excess items chaotically spill to the ground.)

Quality strategies

While it is possible to use quality modules as much as possible and deal with Every tier Everywhere All at Once, here we’ll focus on smaller self-contained systems.

“Gambling”: opportunistic quality without recycling

The easiest but also least effective is to craft from normal-quality ingredients, with quality modules, and not recycle anything. This can be done before unlocking the recycler but is only viable for a small number of items, such as crafting a few hundred asteroid collectors to hope to get a dozen uncommon or rare ones for an early space ship.

This is improved when the factory has another use for normal-quality items. For example if placing thousands of normal-quality solar panels on the ground, crafting them with quality modules gives a better yield of higher-quality ones for space ships before the output buffers fill up.

With a single step and no loop, this is simplest to calculate: the expected product tier distribution is the first row of the transition matrix or of the probability table found on the wiki.

“Washing”: pure recycling loop

For most items, the recycler reverses the main crafting recipe and returns 25% of the ingredients. But some items don’t have a crafting recipe (like ore) or it is considered irreversible (typically smelting and chemical processes). In that case the recycler produces either nothing or, 25% of the time, the same item. This process can improve quality if the recycler has quality modules. Repeating it in a loop, eventually all items will be either destroyed or improved until they reach any desired quality tier. Self-recycling items is arguably not the common case but let’s start here since the math is simpler.

Again we use 5-component row vectors to represent the long-term average throughput of items in each quality at various points of the system:

- items injected into the system, with any quality distribution, in this example based on quality modules in miners

- Items

- All items going through the

- Items based on their quality tier, in this example rare or above

- Items with quality , those not extracted

We treat as a fixed parameter and other vectors as unknowns we want to resolve.

The transition matrices for filtering based on quality tier are complementary parts of the identity matrix. In this example:

When initially built, the system is empty and items start being injected at a constant rate. The rate of items being either destroyed in recycling or extracted is proportional to the total amount, so eventually the system converges to a dynamic equilibrium where the following equations hold for long-term averages:

We can rearrange and substitute:

Transpose to get column vectors instead of row vectors and match the classic convention:

Introduce some new names:

Now we have a system of linear equations in the classic form, that we can solve for using Gaussian elimination. From we can easily compute , then (for the number of recyclers needed) and (for the overall yield of the system).

If the example setup above was scaled to mine 100 ore per second, the parameters would be:

And the solution with Gaussian Elimination:

Converting from per second, the extracted rates are close to 90 per minute rare, 9 per minute epic, and 1 per minute legendary.

For another example:

- Injecting only normal-quality fresh items, for now in some arbitrary unit:

- Recycling with the best available quality modules:

- Extracting only legendary-quality items

Solving the equation gives:

So for items that recycle to themselves, “brute-force” washing consumes on average normal-quality inputs for every legendary output. This matches the ratio that others have calculated. The recycling capacity required is just shy of of the fresh input rate.

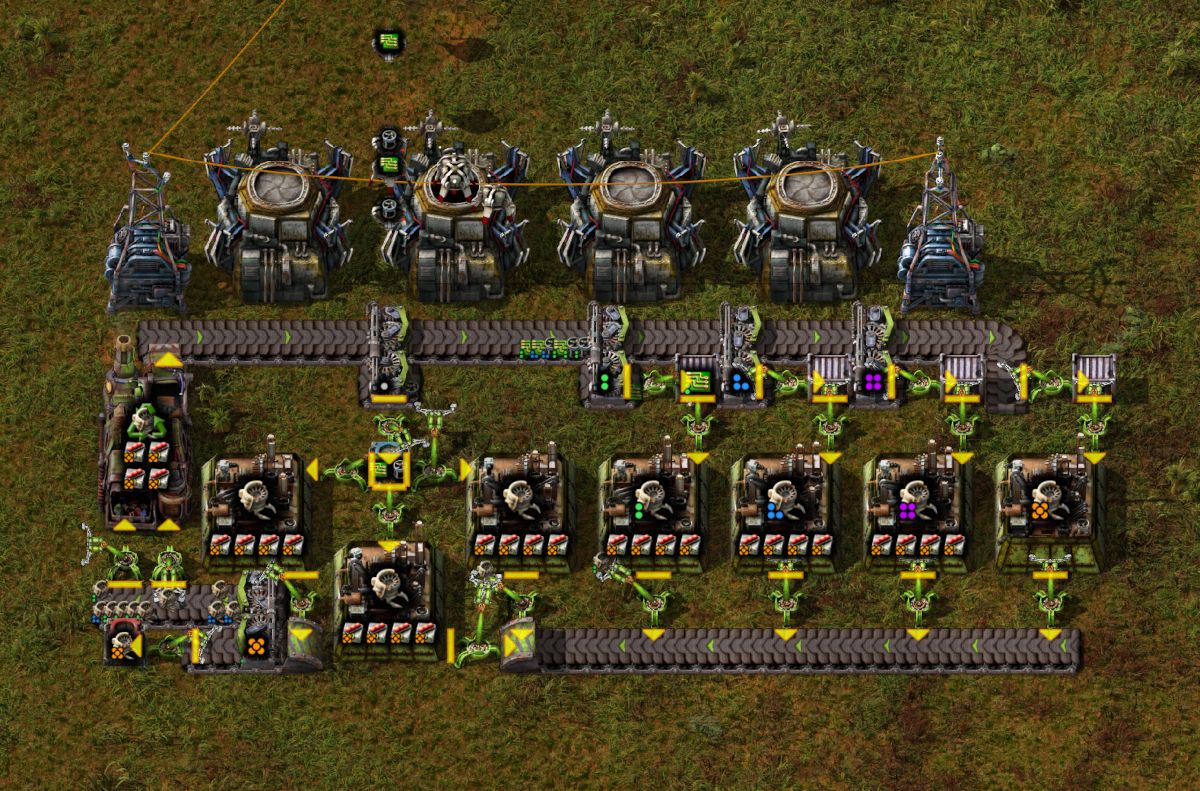

“Upcycling”: crafting + recycling loop

For items where recycling does return ingredients, we can chain crafting machines with recyclers to form a loop:

Most crafting recipes require multiple ingredients in various quantities, but here we’ll abstract over this and consider “the ingredients for one craft” as the base unit for our measurements. In this example, each machine crafting construction robots can consume 4 electronic circuits per second and 2 flying robot frames per second, but we’ll call that “2 ingredients per second”.

So we’re measuring long-term avarage rates of ingredients and products, each in five quality tiers, but they only appear in separate parts of the system so we’ll stick with 5-components vectors and don’t need to move to 10-dimensional math. (Wink wink foreshadowing)

The example setup has fresh normal-quality ingredients brought by robots into the blue requester chest, and extracts legendary products. In the general case, we could imagine ingredients or products of any quality distribution being produced elsewhere and injected into the system. Similarly, we could decide to extract products or ingredients (or both) of any quality tier. Sometimes upcycling a specific item can be a good method for getting some of its ingredients in high quality.

So the 5-component row vectors we’ll consider are, for ingredients:

- injected into the system, with any quality distribution

- Ingredients

- based on their quality tier, in this example none

- Ingredients new products from

And for products:

- injected into the system, with any quality distribution

- Products

- based on their quality tier, in this example lengendary

- Products

We treat and as fixed parameters, and other vectors as unknown we want to resolve.

Again the transition matrices for filtering based on quality tier are complementary parts of the identity matrix. In this example:

We account for a crafting which is in this example but could be greater with some crafting machines or with productivity modules. The quality chance may also be different for crafting v.s. recycling (for example when crafting with productivity modules, or based on the machine’s number of modules slots).

For short(er), let’s call:

The system converges to equilibrium where:

We can rearrange and substitute:

Let’s introduce a couple more names:

We’ve again massaged our problem into the standard form with:

Solving for gives us , and plugging that into the original equilibrium equations gives everything else.

In the example setup above, scaled for now to an arbitrary unit, the parameters are:

And the solution with Gaussian Elimination:

In practice, the bottleneck of this system is the crafting speed of normal-quality products: 360 per minute. So let’s multiply everything by

In conclusion, this system produces on average almost 2 legendary construction robots per minute, and consumes about 309 sets of ingredients (309 frames + 618 circuits) per minute.

For a select few items in Space Age, the productivity bonus can be increased through repeatable research. The game enforces a hard cap of bonus so that crafting then recycling returns at most the ingredients that we started with, never more.

Productivity research levels get exponentially expensive so let’s assume that we use also productivity modules to reach the cap, meaning we don’t have quality modules in crafting machines. And this time, let’s inject fresh products instead of ingredients.

Our model predicts:

Perhaps surprisingly, the rates for intermediate quality tiers are identical.

A maximal productivity bonus enables turning a normal quality product into a legendary one without any ressource loss, at the cost of many machines and modules to get significant throughput.

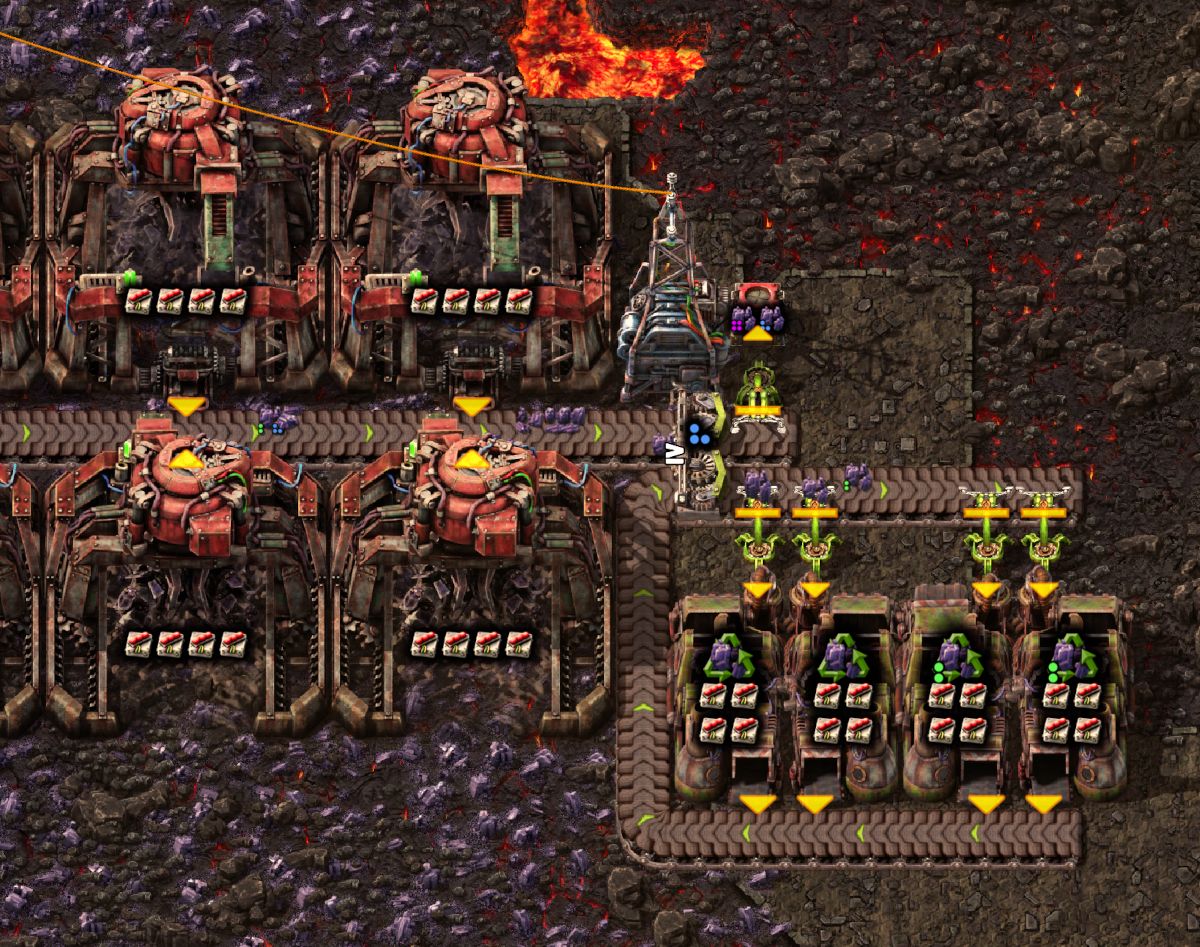

“Space casino”: asteroid reprocessing loop

In Space Age, each space platform is a mini-factory. Instead of mining ore from the ground they collect asteroid chunks and crush them to get resources. Those can be used for a space ship’s own fuel and ammunition, or to feed a production chain in space whose end-product is sent to a planet’s ground.

Three different types of chunks (metallic, carbonic, and oxide) yield different ressources and are more or less frequent in different regions of the solar system. Asteroid chunks can be “reprocessed” for a chance to get a different type (or nothing).

Assuming enough crushers with each recipe, we can represent this process mathematically as multiplying a row vector by a square 3×3 transition matrix:

Reprocessing also accepts quality modules so it can be used in a loop much like “washing”. Crushing legendary chunks yields legendary versions of some base resources that can be used for crafting other legendary items.

This time we’ll have conveyor belts transporting asteroid chunks of any of three types, each in any of five quality tiers, for a total of 15 possible items. We’ll represent this with 15-component row vectors and 15×15 transition matrices. We build up the latter as block matrices made of nine 5×5 blocks:

Aside from the higher dimension, the math is the same as for washing and we end up with a system of linear equations to solve for , with:

Asteroid crushers have two module slots, so the best possible quality chance for reprocessing is . Asteroid collectors don’t have any module slot, so freshly-collected chunks are always normal-quality. We build the 15-component vector from its 3 components for normal-quality rate of each asteroid type (metallic, carbonic, oxide). For example in Nauvis orbit:

Let’s say that we only extract legendary oxide chunks and reprocess everything else. Solving the equation gives two complementary 15-components row vectors and that we can rearrange into 3×5 tables

Example: in Nauvis orbit, extract legendary oxide chunks and reprocess everything else:

| To reprocess | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ⚀ | ⚁ | ⚂ | ⚃ | ⚄ | |

| Metallic | 1.31616 | 0.33791 | 0.13314 | 0.05286 | 0.0175 |

| Carbonic | 1.11409 | 0.33244 | 0.13245 | 0.05277 | 0.01748 |

| Oxide | 0.91202 | 0.32697 | 0.13175 | 0.05268 | 0 |

| Extracted | |||||

| ⚀ | ⚁ | ⚂ | ⚃ | ⚄ | |

| Metallic | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Carbonic | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Oxide | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.01398 |

We observe:

- As the quality tier increases, the distribution of asteroid types quickly converges to an even each. The distribution of normal-quality fresh input has negligible impact on that of legendary-quality chunks going through the system.

- When extracting a single type of legendary asteroids, the legendary yield is about of the total fresh input. This is much better than about for “washing” a.k.a. pure recycling, thanks to reprocessing destroying its input only of the time v.s. for recycling.

Other strategies

There are other ways to get quality items that don’t neatly fit in the categories above (honorable mention to “The LDS Shuffle”) and I’m sure folks will come up with more. But if a loop makes it tricky to calculate their behavior we can use the same ideas:

- Represent throughput of multiple kinds of items as vectors

- Represent linear transformations (crafting, recycling, …) as matrix multiplication

- Represent dynamic equilibrium as a matrix equation

- Solve the equation, using Gaussian Elimination if needed

Making an interactive calculator tool

Doing matrix math by hand is obviously tedious and error-prone, let’s have computers do it for us.

I started with Rust out of habit.

nalgebra works out great for the matrix math we do here.

In includes multiple solvers for systems of linear equations,

but those pretty much require the scalar type for matrix and vector components

to be a floating point number f32 or f64, whereas the base library is more generic.

In practice floating point would be perfectly adequate, but it is a fixed-precision approximation so every step of computation potentially introduces some error. Wouldn’t it be nice to get an exact result, just because we can? The matrix sizes and number of operations are fixed and relatively small, so we don’t need to optimize the code for speed.

Every operation we use is ultimately addition, substraction, multiplication, or division.

So if all of our parameters are rational

the result will be too.

num_rational represents rationals extactly

as a pair of (generic) integers.

I could reach for some infinite-precision BigInt library if needed,

but the built-in i128 with

overflow checks

turns out to be sufficient for 15×15 martices.

(i64 is sufficient for 5×5.)

At this point I had a functional Rust library doing all of the math above, but editing source code to tweak parameters isn’t a nice user experience. I’d much prefer something like Factoriolab. And to be easy to use by other people it really should be on the web.

My Rust code can be compiled to WebAssembly but then I would need to either:

- Build the entire GUI with Rust + wasm as well. It’s possible but the tooling isn’t great yet

- Build the GUI in JavaScript or TypeScript (taking advantage of mature tools) and bridge into wasm for the math. But because of the many parameters the API surface is significant, and doing that much bridging isn’t fun

So I ended up rewriting the whole thing in TypeScript.

BigInt

is built-in,

Factoriolab already has a good open-source

rational library,

and making a generic matrix library isn’t too hard.

As to building an interactive GUI in the browser, last time I did much of it jQuery was the hot new thing. I didn’t feel like learning React so I settled on:

- VanJS for minimal reactive goodness

- Vite for TypeScript wrangling and a reload-on-save dev server

- Grebedoc for static file hosting

All together, factoqual.grebedoc.dev now provides an interactive GUI for planning Quality upcyclers. Its source code is published at codeberg.org/SimonSapin/factoqual.

Acknowledgments

I was heavily inspired by Daniel Monteiro’s blog posts on quality math. Others have done similar work, including Konage and Factorio wiki contributors. As far as I can tell they all rely on iterative approximation, as opposed to the exact solution shown here.